The Economist: China’s mid-sized cities are enjoying a property boom

FOR years Wuhu, a city (pictured) in the poor central province of Anhui, was on the front line of a national effort to reduce a glut of unsold homes. New property developments stretched into the haze along the Yangzi river on the town’s western edge. But buyers were scarce: although Anhui has a population about the size of Italy’s, many of its people have long preferred to work in richer parts of the country. Officials in Wuhu tried to entice locals to buy homes, offering tax breaks. At one point they even promised to subsidise the cost, an act of desperation that made Wuhu an emblem of China’s real-estate woes.

Since early 2016, however, the city’s property prices have soared by more than 30%. Earlier this month the city sharply changed tack, introducing measures to curb speculation. For example, it required that buyers of new homes wait at least two years before selling. Developers were ordered to set prices within predetermined ranges. The city also vowed to expand the land available for development. The glut of unsold homes is, in other words, no more. A shortage is the new concern.

The striking improvement in Wuhu’s property market has echoes around the country. It is one of the 60 or so cities deemed to be “third tier”. The designation refers not just to their political ranking and size (medium by China’s standards, with populations of roughly 1m-3m); until recently it also summed up prevailing sentiment about their prospects. Analysts and investors have generally been positive about China’s first-tier megacities (Beijing, Shanghai, Shenzhen and Guangzhou) and its second-tier giants, especially those in good locations such as Hangzhou in the east and Foshan in the south. But there was less enthusiasm for cities ranked in the third tier and below. They were seen as suffering from weak industrial bases, flimsy social services and a steady brain-drain as their most educated residents left for more exciting places.

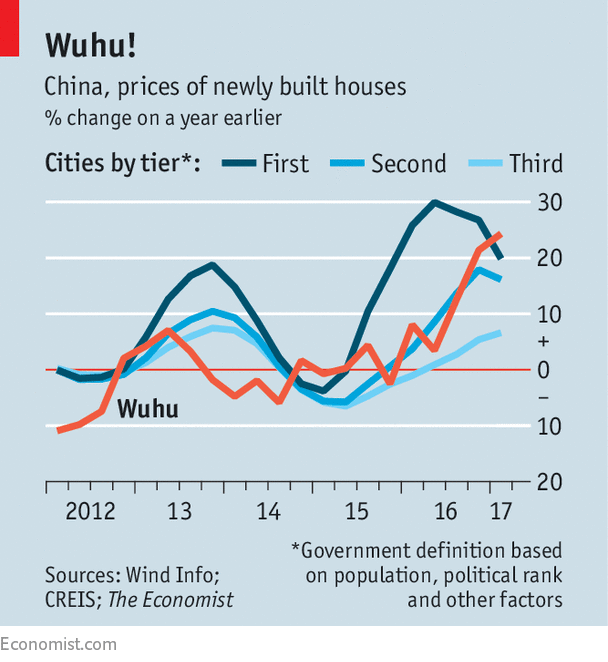

Yet a rally in China’s property market, which began in its big cities in 2015, is filtering down to these also-rans. Housing prices in third-tier cities are up by 7% over the past year on average, and by much more in the best performers (see chart). Their markets have remained hot this year, even while their bigger peers have cooled off. This has helped to reduce the stock of unsold homes. The amount of housing for sale has fallen almost continuously for the past 14 months, the longest sustained decline since records began in 2001.

That would seem to be unambiguously good news. But a closer look at third-tier cities suggests caution is in order. Speculation has played a large role in their new-found prominence. Capital controls, progressively tightened over the past two years, have trapped cash in the country. After a stockmarket collapse in 2015, housing became the most appealing asset—all the more so when, to boost the economy, the government began encouraging state-run banks to increase their mortgage lending to homebuyers. After a run-up in prices in big cities, investors looked to smaller markets for bargains.

Recent government efforts to douse the fervour in big cities had a similar effect. When Hefei, Anhui’s capital, started restricting purchases last year, buyers rushed elsewhere, including to Wuhu. Li Guochang, head of a property-research institute in Anhui, estimates that people from outside Wuhu account for more than a quarter of purchases this year, up from the normal level of about a tenth. There are now roughly 20% more homes owned in Wuhu than there are households in the city, he says. As he puts it: “This doesn’t seem very healthy.”

Nevertheless, it is too easy to treat the rally in third-tier cities as froth. Owner-occupiers make up a majority of the market. Many are locals who have the means to move to nicer homes, tired of the shabby six-floor walk-ups that still dominate many old city-centres. As for speculators, they might just know a thing or two. It has been striking that the price surge in third-tier cities has not been evenly spread around China, but rather concentrated in markets that have better locations. Places that fall within the gravitational pull of the most prosperous cities, particularly in the east and south, have fared the best. But thanks to better infrastructure links, there are many more locations that can be defined as good. Wuhu used to be a backwater. Today it is less than three hours from Shanghai by high-speed rail. In the north and west of China, well away from its glittering coast, housing prices are about the same as they were five years ago.

Homeward bound

A cascade of development has also changed the economies of mid-sized cities. As land prices and wages have risen along the coast, companies have moved inland. Wuhu, for example, now boasts numerous robotics firms. Population flows are changing, too. Anhui is one of the main sources of the migrants who staff factories and work on construction sites around the country. But its permanent population has risen by 1.7m since 2014, buoyed by the return of some of its migrant workers.

Similar reversals are also occurring in two other big out-migration provinces: Sichuan in the south-west and Hunan, Anhui’s neighbour. Some migrants are returning because of old age—the government restricts their access to health care and other benefits in places other than where they were born (to control prices, some cities have recently limited their ability to buy homes, too). Others are lured by an improvement in job opportunities. A teacher at a vocational college in Wuhu says most of his students now stay put.

The central government wants to promote this trend: it believes it will help it achieve its goal of curbing the growth of the biggest cities. Shanghai’s population has nearly doubled since 1990, to 24m. Between now and 2040, the city is aiming for a maximum of 1m more residents. Smaller cities, meanwhile, are being encouraged to attract outsiders. Some, such as Wuhu, offer special grants to university graduates who choose to live in them.

China’s campaign to control city sizes may end up causing economic harm, placing artificial limits on the most productive urban centres. It is also deeply unfair to migrants from the countryside who have toiled for years in big cities but who have little hope of settling down permanently in them . But Wuhu and its third-tier brethren are not complaining: the restrictions, loathed by so many, are helping to give them life.